“If a warrior is not unattached to life and death, he will be of no use whatsoever. The saying that “All abilities come from one mind” sounds as though it has to do with sentient matters, but it is in fact a matter of being unattached to life and death. With such non-attachment one can accomplish any feat.”

“Even if it seems certain that you will lose, retaliate. Neither wisdom nor technique has a place in this. A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death. By doing this, you will awaken from your dreams.”

“Bushido is realized in the presence of death. This means choosing death whenever there is a choice between life and death. There is no other reasoning.”

― Tsunetomo Yamamoto, Hagakure.

My Interest on Japanese Cinema

If you read one of my previous post you know about my Love Affair with Cinema (Jan 2017) as a child, and a young man, not that I ever stop of loving movies, but you could say, I have not the time now to waste, as I did as a young man, looking at movies, that unfortunately, sad to say, most of them are a waste of time, mass produced, poor in plot, and most of the time mindless entertainment, despite the great amount of money now day cost producing a movie, save few honorable exceptions of course.

From very early in my life I was impressed with Japanese cinema by the portrayal of fearless, skillful with a sword, and honorable Samurais, willing to give their life away for loyalty, and their high moral sense of duty.

How not to be impressed by these stoic warriors, heroes of the past, at such tender, and idealistic age?

Not to say the movies were superbly crafted, and carried by a vision different from let’s say a bunch of wild, and rogue, cowboys, and bank robbers, in a saloon brawl, exciting as it may be, but stories devoid of idealism, and selflessness, characteristic of Samurai’s Bushido code movies, as we used to call them, how can we forget the Judo Saga 1965 by Seiichiiro Uchikawa, first made by Kurosawa in 1943 the story of Sanchiro Sugata but not available until much later (1974), or Hiroshi Inagaki’s superb Samurai Trilogy 1954-1956, and his Chushingura Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki. 1962. just to mention some of the few most memorable Japanese movies I recollect, as writing this, from the many I saw.

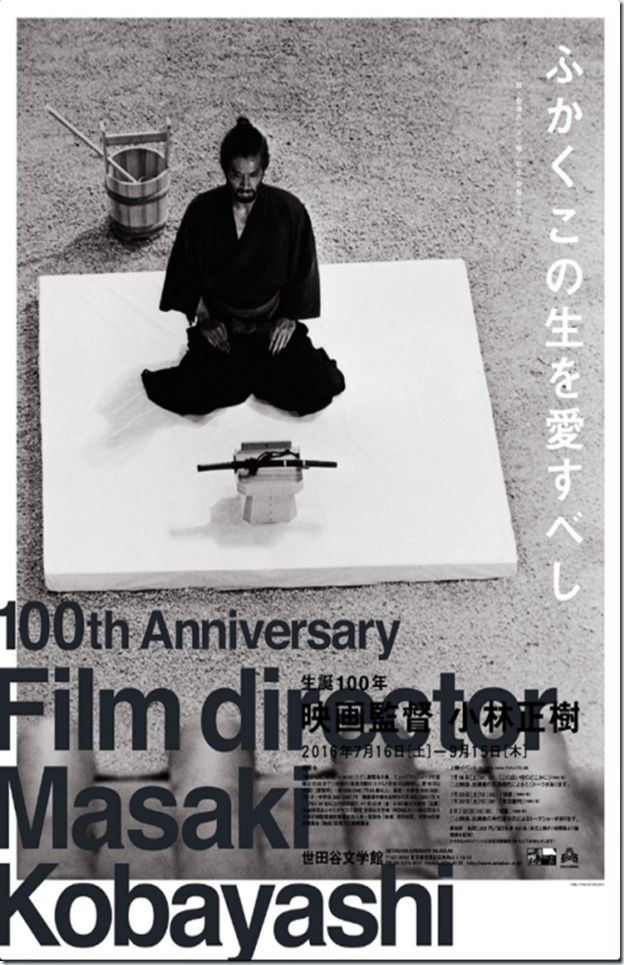

Masaki Kobayashi

There is many Japanese movies I watched worth writing about it, however for today I will talk about Masaki Kobayashi who impressed my young mind by some great movies he made, and now looking back for his great social vision somehow overlooked in the West, by our lack of sympathy rampant at the time, with a fear of communism, fresh out of Senator McCarthy reign of terror, McCarthyism was a widespread social and cultural phenomenon that affected all levels of society and was the source of a great deal of debate and conflict in the United States, Kobayashi despite the prices, and nominations he won, is work now days lay forgotten, but for a few cognoscenti of this great director.

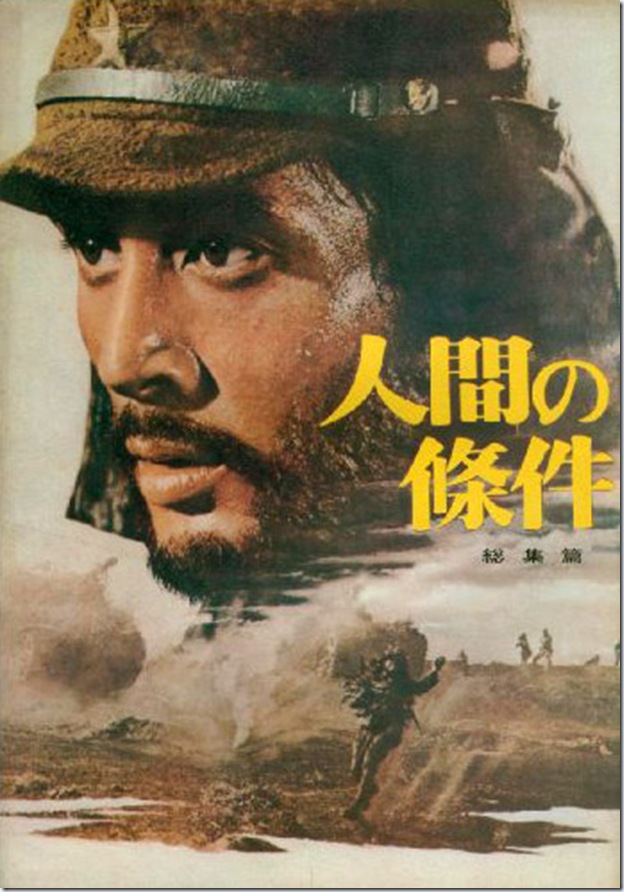

Masaki Kobayashi (小林 正樹 Kobayashi Masaki?, February 14, 1916 – October 4, 1996) was a Japanese film director, best known for the epic trilogy The Human Condition (1959–1961), the samurai film Seppuku (1962), Ghost Stories (1964). And Samurai rebellion (1967)

An art history student, Kobayashi decided to take up film making when the Pacific war broke out, convinced that cinema was a more urgent medium for a time of crisis. Mere months after securing an apprenticeship at the Shochiku studio, he was conscripted into the Japanese Army in Manchuria, where, as an act of resistance, he refused to rise above the rank of private. He was eventually interned at a prisoner-of-war camp in Okinawa.

Kobayashi’s experiences in that war, which he called “the culmination of human evil,” directly inspired his grueling magnum opus “The Human Condition” (1959-61), a three-part, 9 1/2-hour epic about a principled soldier who decries but becomes implicated in his country’s militarist aggression. Now known principally for “The Human Condition” and such later period films as “Harakiri” (1963), Kobayashi was a clear-eyed social critic from early in his career.

A Rebel, And a Critic

Masaki Kobayashi’s career started during, and through Golden Age of Japanese cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, and all the way to the mid 1980s . Kobayashi has been largely forgotten but for a few cinema lovers around the World, even in Japan interest in his work is much lower than it is for the films of his contemporaries, such as Akira Kurosawa. Despite the fact that some of his films such as the war trilogy Ningen no jōken (The Human Condition, 1959-1961) and Seppuku (Harakiri, 1962) had won international critical acclaim,1 the centenary of his birth in February 2016 passed almost unnoticed in the Western media. The reason for this unpardonable oversight by film goers, and critics alike, it’s easy to understand, some, or I should say many may find his movies, dark, and depressing, others may feel uncomfortable about his political views, and too critical for its day, from a time like the early fifties, specially in Japan, you basically conformed to the establishment of the day, or you were not even be able to work, or even to speak your mind, without risking retribution, and boycott, to Kobayashi’s credit not only he created great cinematography, but condemn Japan Imperial war past, and the uncritical authority from the ruler class of medieval Japan, over their serfs, that didn’t Historically ended, until quite recently, and even today not quite totally extinct in modern Japan, the Daimyo (Lord), now day supplanted by the Company boss.

Thank you very much, Mr Bigido, for this great post about Japan its films, filmmakers, such as Masaki Kobayashi and the code of etiquettes. I remember when we were in Japan in 1975 we went into a restaurant to have super and my husband didn’t have a jacket and that was not allowed! They didn’t, however, send us away but brought us one to use for the time we were there Very best regards Martina

Japan it’s a society, where rules of propriety, and courtesy are paramount, and you are expected to behave accordingly, perhaps in a way that no other country in the World does, when I was a student from my Sensei, everything was done in a special way differently as to what I was used to, from sweeping the floor with a broom, to squeeze a wet rag, or carry a vase, and was taught how to carry any operation the way the Japanese do, like sliding open a screen door, to go through from one room to the other, or how to hold a cup, which it’s different for men, and women, just to give you a few examples, there is the proper way, and many wrong ways to do anything!

Thank you Martina for your comment! 🙂

I very much appreciate your answer and can really feel the differences between our society and that of the Japonese.I also tried to find out more about “Sensei” (representing father and mother= teacher?) I am not sure, if this is correct. All the best. :)Martina

Sensei it’s a word in Japan that signifies Teacher, it could be a formal Teacher, or any you may learn from, Japan was a feudal society, far longer than any other country, except China, in Europe there where the Guilds In medieval cities, craftsmen tended to form associations based on their trades, confraternities of textile workers, masons, carpenters, carvers, glass workers, each of whom controlled secrets of traditionally imparted technology, the “arts” or “mysteries” of their crafts. Usually the founders were free independent master craftsmen who hired apprentices.

In Japan this practices are still used, you go to a Sensei, and request admission to his/her school, if admitted, you may not, then you apprentice with them a craft , an art, or whatever they would be teaching you, and you do as the Sensei says, no arguments, or questions, there is no such a thing, as: “I do not agree.” or “Maybe we should do this different.”

You are there to do as you are told, and expected to do accordingly, you have to try your utmost in order to learn, and behave properly, period.

If you are interested in this subject you can read more on my post of June 2016 Mastery, And The Meaning of Practice.

Thank you for your interest Martina. 🙂

Many thanks for all these information and I think it would do us no harm, if we relearnt to just accept what a teacher says!! I wish you a very good week. Best regards Martina

Yes, in our Western societies we encourage freedom, but too permissive in areas where experience knows better, our youth has now too much choices, at an age where are not ready to deal with responsibility, and freedom. Maybe a little bit of both will be better. 🙂

🌷🌺💐👍

Pretty fascinating. This is not a subject I know a lot about so I particularly enjoyed your post.

Thank you for your comment Vanessa, we appreciate it! 🙂

This is a really good and interesting post

Thank you for your comment, I am glad you find it interesting. 🙂

Bushido

It certainly is a creed for the warrior. It is a religion of sorts. But not a religion of service to humankind. For example I suppose a Christian best absorb this philosophy in time of war but in war only. It is not a moral compass for life: a life to serve humanity , cause no harm and to integrate with Creator.

Well it’s not a Religion, but a code of Ethics, and a Medieval one, sort like our Western societies had in the Middle ages, Chivalry the idealization of the cavalryman, involving military bravery, individual training, and service to others. in Europe has been refined to emphasize social and moral virtues more generally. The code of chivalry, as it stood by the Late Middle Ages, was a moral system which combined a warrior ethos, knightly piety, and courtly manners, all conspiring to establish a notion of honor and nobility.

In Japan a Feudal society for several centuries more than the West, now Japan embracing Modernity and Post-Modernity, and specially after the defeat of WWII it’s not viewed as before, however remnants of it survive to this day.

However the whole idea of Kobayashi’s movies it’s a critic, and condemnation of the system of Bushido, so disastrous to the Japanese in WWII. He personally suffered as a conscript, the consequences of such antiquated, and corrupted system, and expose it’s hypocrisy in his movies.

Thank you Carl for your comment! 🙂

So interesting to learn about other cultures and subcultures.

I am glad you find it interesting, thank you for your comment. Georgia 🙂

Excellent reporting on Japanese films. I realize they are well done,but since my high school years were during WW!!, and those memories were filled with the brutality of the Japanese army, I cannot be dispassionate about anything to do with that country. To me, their insistence on good manners is a mask.

Well, actually Kobayashi will be in complete agreement with you, he was drafted as a young man into the Japanese army, and sent to Manchuria where he resisted the brutality of the Japanese army, Kobayashi regarded himself as a pacifist. His way of resisting was to refuse promotion to a rank higher than private.

The Human Condition his trilogy ten hours long, it’s a condemnation of the Japanese army, and it’s brutality, most of his movies he condemns the old warrior mentality, and rejects any idea that there was anything in it of honorable, or good.

Thank you for your comment! 🙂

Thank you for introducing me to this film director who I admit to not having known about before reading your post here! I have not watched a lot of Japanese cinema. Like you these days I often turn to books instead 😉 It sounds like Kobayashi did not care what was “in style” or criticized and instead marched to his own drum and for that I say “hoorah!” as so many people just want to be sheep in the crowd. Wonderfully written and great use of photos to illustrate your points too xx

Do not worry about not knowing Kobayashi, his heyday was late fifties, and early sixties, over fifty years ago, in my town there was no TV yet, and for fun you would go to the beach on the mornings, and to the theaters in the afternoon to escape the heat of the day on the air conditioned, cool spacious old theaters to watch a double, or a triple feature, before going home, to my books.

I expose Kobayashi, like I can do many other directors worth remembering, now forgotten, in a World who mainly care at was happening right now, forgetting those who preceded them, hey we all live our Zeitgeist.

There are here, and there few people who may know him yet, and other curious enough to look for it.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment Christy! 🙂

Very interesting. I will have to try and locate “The Human Condition”. Your characterization of the books/film trilogy as anti-war is at striking odds w/ the quote about always retaliating and choosing death. The contrast highlights the prevailing cultural view and Kobayashi’s resistance to it. Nicely done.

Criterion collection has it, I am sure Amazon may have it, I got a Barnes & Noble near me, and I saw it there some weeks ago.

Well, Masaki Kobayashi goes against the grain in Japan, because he was conscripted in the Japanese Army, in 1941 and sent to Manchuria, where he suffered a lot, not only the hard , stupid brutality of his own Army being a simple private, but the imprisonment in Okinawa.

I saw this trilogy first, when I was very young ( No more than 12 at most) and impressed the hell out of me, the movies are very sad, and dark, as a matter of fact all his movies are impregnated by a pathos, and are not easy to watch specially for those who are just looking for just fun, and entertainment, he show us the bitter side of life, I guess you can call his movies tragedies.

As for having quotes of Hagakure as a contrast to his work, I thought it was necessary to show the Japanese mentality of Bushido, in order to understand their actions, if you read above some of the comments condemn the brutality of the Japanese Army, and question the Bushido code of the Japanese, and that’s exactly what Kobayashi’s work it’s all about, a condemnation, and exposure of that system of conduct, who ruled in Japan for far too long, and still is glorified by some.

Thank you for your interest, and nice comment. 🙂

Japan has always created some special and monumental movies. The Japanese filmmakers sure have their own visual language. A great post.

Yes, they do, I love some of the old directors, specially the black & white age movies they did, even some color ones, like Hiroshi Inagaki’s Musashi’s trilogy, or Goyokin, by Hideo Gosha, that they come to mind.

Otto, thank you for your comment! 🙂

Japanese cinema was an excellent introduction to Japanese history, culture, language, old traditions, and unique architecture and writing. Ironically I just watched Seven Samurai a week ago (a Kurosawa film.) Many thanx for sharing this post with its info.

Thank you for your interest on my post, yes I agree with you, an excellent introduction to Japanese culture, through watching their movies. 🙂

“Choosing death whenever there is a choice between life and death”? Impressive. It does sum up a lot about Japanese culture. Thank you for this insight.

Brian

Although the samurai made up only a small segment of the population in feudal Japan, their ethos has since been soldered onto the national identity, and Tsunetomo Yamamoto’s, Hagakure, it’s the essence of that Spirit, regardless if today makes any sense.

Thank you for your comment. 🙂

You’re most welcome. I think it is a good example of a small group setting an example in the general population. 🙂

Perhaps you already know the work of Prof. Brian Victoria about the strong relation between Zen and German facism: https://minahasato.wordpress.com/2011/09/17/perversion/

Even if not acquainted until now, that you call my attention with Professor Brian Victoria, I am very familiar with Eugene Herrigel, and Karlfried Graf Dürckheim life and works, and their Nazi past, also with Zen Buddhism, and the Samurai affinity with it, and not the least as an avid reader of WWII History, having grown up just during its aftermath, I am even familiar with Albert Speer. quote on Hitler’s

” Why did not we have the religion of the Japanese, who regards sacrifice for the Fatherland as the highest good? ”

I am also a little bit cynical, and critical of Westerners embracing Buddhism naively believing it fits their postmodern scientific, secular oriented, and ontological conceptual ideas about self. Ignoring Buddhism factual religious underpinnings, and dogmas, if different in nature, not unlike as those from any other religion like Christianity. Dogmas, and rituals that they decided to abandon as an impediment to their new gains as free thinkers, and champions of secular freedom.

As for the Nazis, and Japanese Imperialist been a despicable sort, there’s no doubt about it. But I am afraid I am no sympathizer of War, or violence now days, even by those who claim the virtue that they fight for freedom, and peace, and bless their armies and weapons, with the flag of God, as the crusaders of old times, War remains a barbarity that should be totally abolished, and confine to History books, even if that sound like an unlikely event in the near future.

As for Kobayashi’s films he is one of the harshest critics of Bushido’s Imperial past, and in his films he makes a mockery of the hypocrisy of those upholders of the Bushido code, who without compassion perpetuated horrific crimes, in it’s name.

Thank you for your comment. 🙂

Nice to find a similar soul!

They just convicted a German Buddhist priest for child abuse in Germany.

It means: Nothing is perfect, but so many people are always ready to follow something which does look like it.

In every religion, and I should add, wherever there is a relation of power, and obedience such things unfortunately happen: Errare humanum est, sed perseverare diabolicum.

Thank you.